The Importance of CMF

In just 7 seconds, 32% of the people will take function as the main purchasing factor, 20% will choose price, the remaining 8% will be affected by other factors, and 40% will choose products according to appearance. Generally, colour, material and finishing process are the most important and intuitive elements that affect the appearance. This shows that before using a product, “users will judge whether they are interested in it through the colour, material and finishing process of the product” (Liu, 2017:133). Facing the same product function and price, most consumers will determine their purchase behaviour based on the appearance of the product and our subjective feelings. Therefore, it can be thought that CMF is the most expressive part of a product and the most infectious element for users (Liu, 2020:858).

No more is the importance of CMF illustrated than in user studies conducted by Raymont-Osman as part of product development on a recent device. When questioned, interviewees unanimously indicated that one competitor product was better than the rest. Despite this, when asked to choose which product they would purchase, one participant selected a completely different device based on their favourite colour scheme! Case and point!

When considering CMF, it is common to only think about the aesthetic of the product and there is no denying that it does play a key role here. However, CMF is fundamentally so much more than just what a product ends up looking like. Rather, it is incorporated into some of the key design and manufacturing decisions and considerations, which ultimately determine whether a product is a success or not, whether it fits the needs of the user, is accessible or actually functions in its intended environment. These are just a few of the things that should to be considered when employing CMF as a design tool.

Colour

Colour choice has a significant influence on a user's decision to purchase a product; this can sometimes be more influential than function or cost. It is incredible how many practical factors a customer can overlook in favour of their own personal taste! Colour can be deeply personal - our dress sense, how we decorate our home for example - are all unique.

Colour has the power to provoke an emotional response from users. Colour theory suggests that certain colours resonate with us in certain ways, usually on a subconscious level. This means that colour can be used as a tool to manipulate the emotions of the user and thus create a more personal experience.

Examples include:

- Navy blue - when people see navy, it often provokes feelings of power, dependability and authority; great for prestigious, serious projects, but maybe not so great for a children’s toy.

- Brown - the colour of earth, wood, and stone, brown is a stabilizing and warm colour with the ability to bring a grounded naturalism to designs.

- Yellow - evokes the most contradictory emotions. On the one hand, people perceive yellow as a light, joyful and sunny colour, on the other hand, it symbolizes betrayal. Whilst, it is usually perceived positively, it should be remembered that the excess of this colour in the environment may cause discomfort in some people.

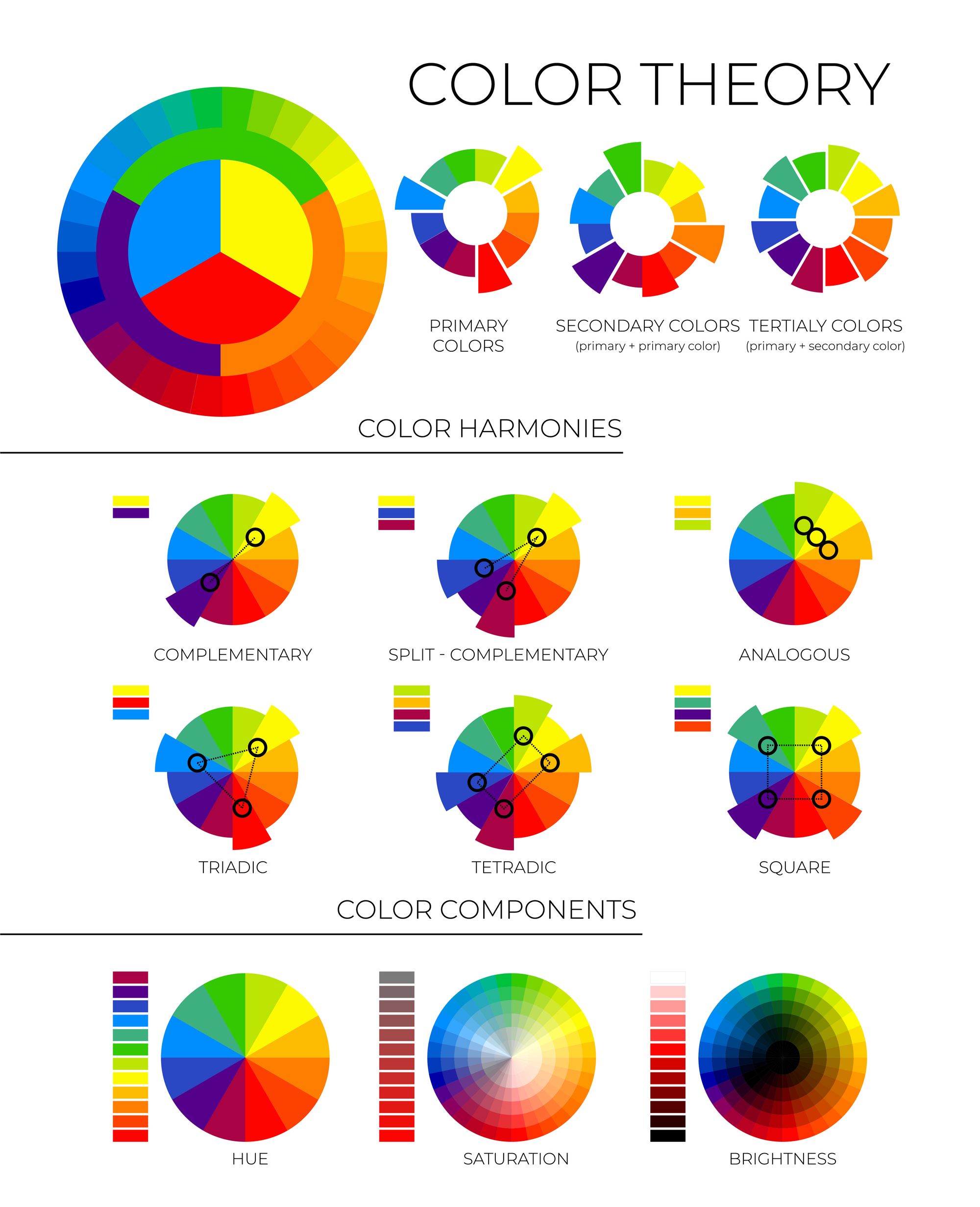

Colour Theory combines Science and Art. It explains how humans perceive colour; and the visual effects of how colours mix, match or contrast with each other. Colour theory also involves the messages colours communicate; and the methods used to replicate colour.

In colour theory, colours are organized on a colour wheel and grouped into 3 categories: primary colours, secondary colours and tertiary colours.

But, as Product Designers, how can we utilise Colour Theory to optimise branding, marketing and ultimately, sales?

An understanding of colour can inform effective design decisions; all by drilling down into our psychology. Questions such as:

- What emotions does a colourway evoke in the consumer?

- Does it match the targeted demographic?

- Will the colour pallet age well?

- Is it accessible or fit for a specific purpose?

With this knowledge, our Designers can advise you on key branding decisions aimed specifically at your consumers. Poor colour choices can equate to poor sales. Using the psychology of colour, we can match the use of colour and contrast, with the emotional responses we wish to evoke in the end-user. Through UX (User Experience) research, Designers can fine-tune colour choices to best target consumers and their expectations. Usability testing will then confirm your colour choices before any costly investment.

Colour Theory Caveats; there are a couple of important caveats regarding any decisions on colour you make for your product. These include:

- Design for Accessibility - more on this below, but this includes considerations such as visibility in different environments such as the dark, or colour-blindness.

- Geographical and Cultural Variations - Not all colours evoke the same response worldwide, for example, take the colour red: good fortune in China, mourning in South Africa, danger/sexiness in the USA.

Usability testing against your target market is therefore crucial.

Colour is more than a question of personal taste, however, it is often used to convey a message to the user and doesn’t account for personal taste at all. It is appropriate in this application because it is not about convincing the user to make a purchase but rather to provide them with information quickly, sometimes just at a glance. An example of this, is when looking for tourist destinations on the road UK motorists should know to look out for brown signs, or hi-visibility clothing or equipment designed to make objects highly visible. When designing safety critical systems, colour should be used with caution, with personal taste not coming in to decisions. Frequently there will be certain standards to adhere to regarding colour and these will effectively make your decisions for you.

Material

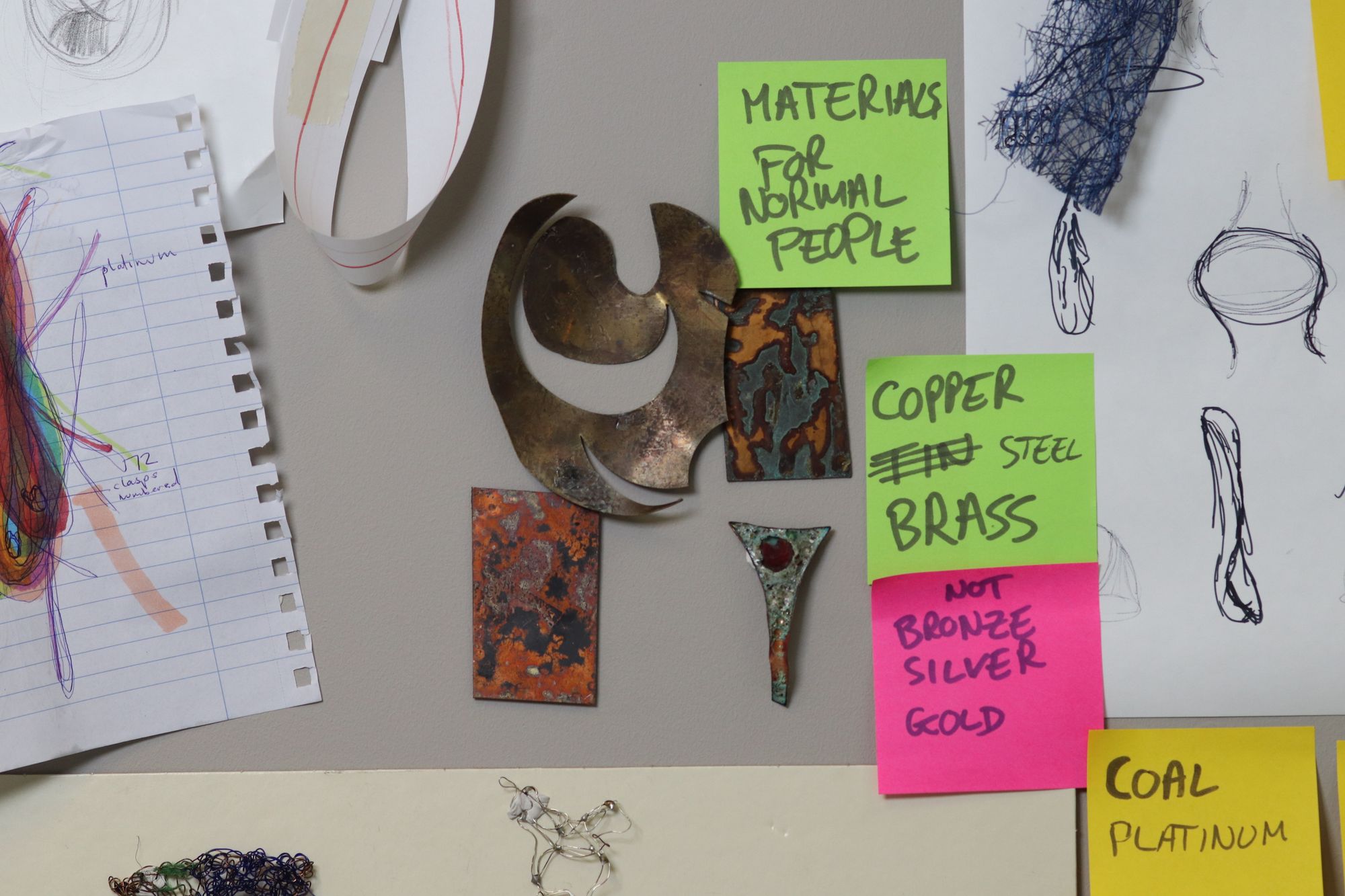

The material specification for a product plays a big role in both functionality and ultimate product cost. The variation in material properties can also be used to amplify the performance of products, depending on their function. By drilling down into the main function of the product, you can then decide which materials are most suitable for that purpose.

Variants, such as operational temperature, manufacturability and cost, will inform the design and influence which aspects to develop moving forward in the design for manufacture process. Whether a product is durable or fragile and behaves as it needs to in its intended user scenario depends heavily on the materials it is constructed from. Beyond look and feel, materials are critical for optimising functional aspects of a product like ergonomics or ease of cleaning; when designing a medical product for example, this is crucial, or the device will not be deemed fit for us, no matter how aesthetically pleasing it is. Designers often begin with specifications detailing all that a product needs to do, before making any material decisions. Designers and Engineers take great care to make sure CMF choices made during product development are aligned with the context and expectations of end use.

Our Product Designers and Engineers have years of experience in analysing materials and identifying the right product materials that function perfectly and solve problems - often utilising different textiles, metals, woods, plastics and woven to create beautiful products. Effective materials strategy has the power to make or break your product. For example, take the design of the gaskets on a pair of goggles. These need to be soft, flexible and must conform to the shapes of eye sockets. Material was selected according to its adhesive properties to bond to the polycarbonate lenses during the injection moulding process. A soft, smooth surface finish feels good to users, especially when in contact with sensitive areas such as that around the eyes and preventing the faint goggle-induced circles under the eyes, known as 'goggle eyes' or 'panda eyes'.

An appreciation of operational environment is crucial to the success of a product. In the case of the goggles, Raymont-Osman and Speedo Designers worked tirelessly to select the appropriate materials to withstand a warm, wet / damp, chlorine-filled environment. Given the sensitivity of eyes and the propensity for mould-growth in this sort of environment, antimicrobial materials were selected to prevent rotting and the risk of eye infections.

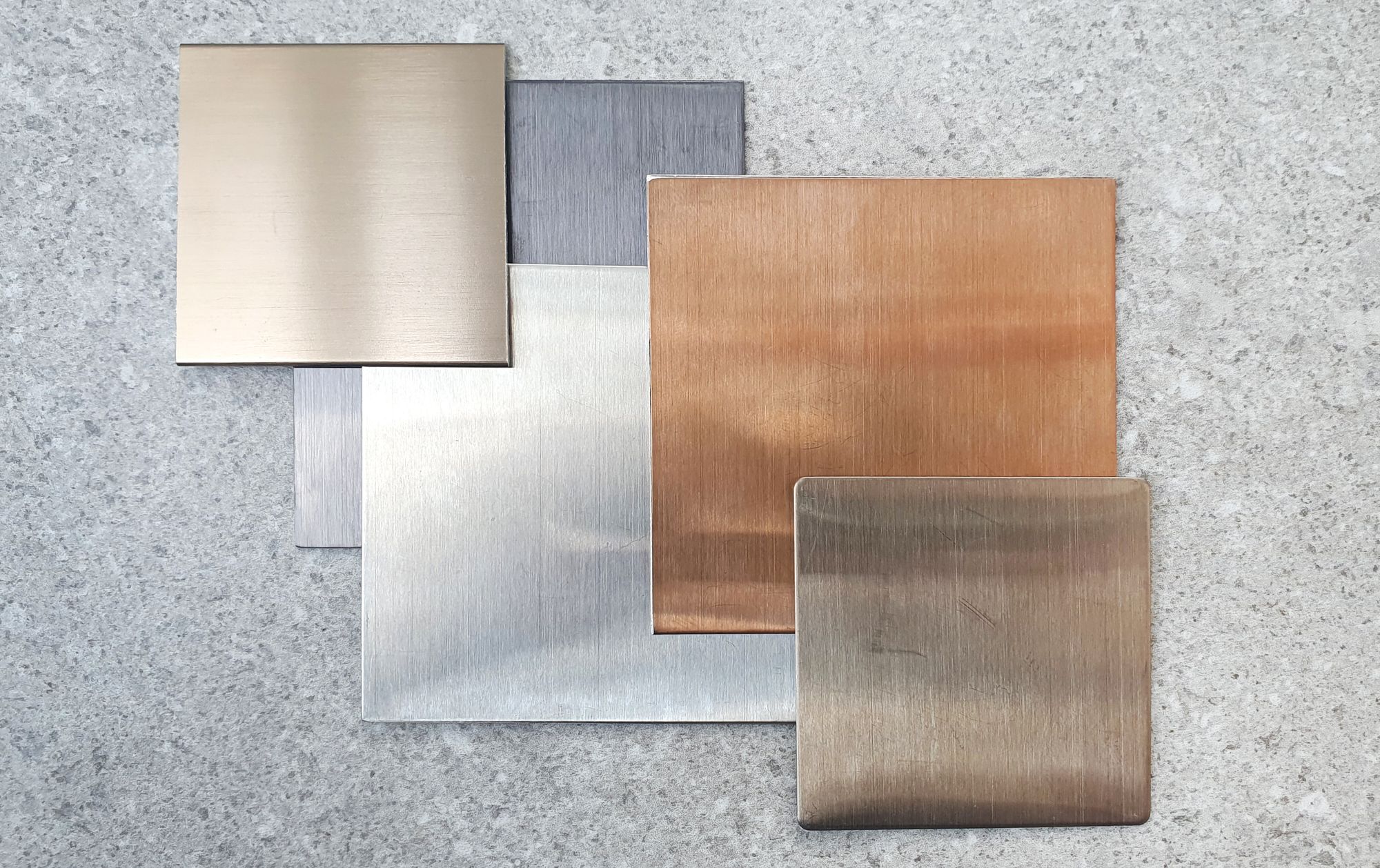

Aside from functionality, the material selection can also play into how a product feels in the hands of the consumer, including evoking perceptions of quality and value. Does the product feel cheap or luxurious, robust or fragile? These are all questions you need to ask yourself when making materials selections.

Understanding a material's manufacturing potential is key to Product Designers. At Raymont-Osman, our experts possess world-class knowledge of the intrinsic properties of materials and their manufacturability. Today, among the criteria for choosing materials, the emphasis has shifted more towards considering economic aspects and environmental impact, both of which are intrinsically linked to the manufacturing process. Aluminium for instance is more expensive pound-for-pound to manufacture than steel, but as it is easier to manufacture, it can mean that you need to use less of it within a product, carrying obvious monetary implications.

Working closely with our clients' preferred manufacturers, we can design products from materials which match their manufacturing processes and equipment, not to mention their budgets. Take our design work on the RAW Artificial Athlete Sportsfield Density Tester as an example. RO Designers and Engineers opted for aluminium over other metals such as steel for a variety of reasons; easy to machine, light and recyclable, the use of aluminium matches the user requirements of portability, whilst being relatively corrosion resistant in a mainly harsh, outdoor environment.

The selection and combination of materials is also greatly influenced by sustainability. Considerations such as how the product will be assembles, used, and later discarded all feed into the original materials selection. Using new materials and discovering more sustainable processes can change the entire design approach as well as the final product. There are a number of ways in which Designers can produce products with an eye to promoting greater sustainability. These include:

- Reducing the number of different types of plastics in a product to make it easier to recycle without much disassembly.

- Performing a Life Cycle Analysis - the process of performing an environmental evaluation of a product’s development during each stage of its useful life including: the extraction of the raw materials, refining of raw materials, fabrication and packaging the final product, proper reuse, recycling and disposal of the product at the end of its life cycle.

- Life cycle testing, including the number of cycles to failure, is critical to understand various modes of failure and improve overall design and materials selection. The longer a product can be in use, the fewer products need to be manufactured and decommissioned.

- Reducing the amount of raw materials used to make a product.

- Reducing the number of components.

- Selecting materials which reduce the products energy requirements during manufacture and use.

- Maximize the use of renewable and recyclable materials.

- Designing for modularity - rather than needing to dispose of the whole product when one component fails, designing for the replacement and availability of individual parts.

Finish

There is a great variety of material finishing processes and these can be just as important as choices made around materials or colour.

Beyond technical properties, the finish on a product can have a sensorial aspect that helps elevate the intrinsic value of a product in the mind of the consumer. How a material feels in the hand of the consumer is another contributing factor to a customer’s associations with a product. Plastic is usually cheaper and easier to manufacture, but can often be associated with poor quality products, whereas, materials such as steel are predominantly harder and more expensive to manufacture, but more commonly associated with quality and durability. This can be overcome by using different finishes or changing the weight of the product to imply quality. Adding weight can imply quality when using less costly materials. However, this should be applied on a case-by-case basis, for example, adding weight to a smart wearable item may not achieve the desirable outcome when most competitive products are designed to be lighter and thinner. Other techniques such as powder-coating, vapour blasting, over-moulding and painting are also examples of how the finish of a product can influence the aesthetic, feel and perception of value of a product.

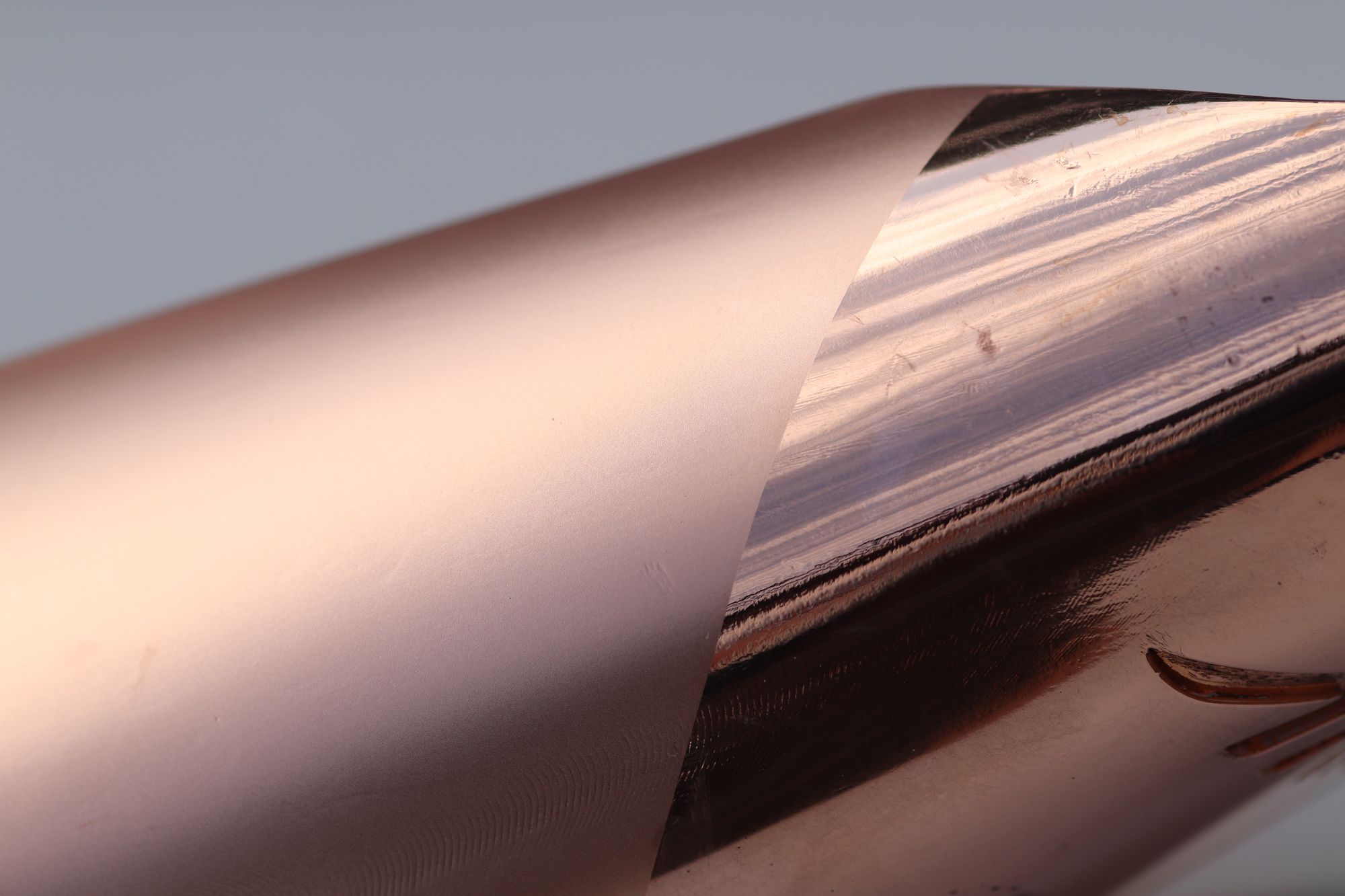

When users make assumptions of perceived value based on finish, they tend to associate higher value with increased time-intensity involved in the manufacturing process, high levels of intricacy, complexity or uniqueness. Hand-made products, which cannot be exactly replicated, made from natural materials such as wood, ceramics, glass and silk, are generally perceived to be of higher value than mass produced consumer products. As a result of the rise in industrialised manufacturing processes, "the value of hand-made products has skyrocketed within recent years, especially if it involves legendary materials or traditional making processes" (Becerra:142). The ability of a product to withstand wearing-in is also highly sought-after, especially in Western culture. Jewellery, watches, furniture and other heirlooms are designed to become iconic pieces, that can be handed down through the generations. As such, materials and their finishes are expected to develop some kind of patina, and become softer or discoloured as they wear-in.

When designing and developing the Queen's Baton for the Birmingham 2022 Commonwealth Games, Designers at Raymont-Osman spent considerable time considering material finish in a bid to convey value. The desire to create a bespoke, organic piece influenced by the touch of the tens of thousands of Commonwealth Citizens it came into contact with, heavily affected our decision to opt for vapour-blasted copper. Blasted to create a smooth, matt finish, the chemical properties of the copper enable it to oxidise to form beautiful blue/green patination; a process which is further enhanced by contact with water and salt (including the sweat from the many hands it came into contact with!!!). By choosing not to apply a lacquer finish to the copper, RO Designers created a design which evolved over time, creating a sensorial experience in the minds of the end-user.

In Summary...

CMF has the power to change perceptions of a product; from a subtle to loud, safe to dangerous, contemporary to heritage, cheap to luxurious.....and anything in between. Given its ability to alter your customers' interactions with your product - or indeed whether they choose to interact with it at all! - CMF should always be considered within the design process as an integral component and not merely a bolt-on.

A great place to start when thinking about CMF is to consider the values you want espouse - both as a business or brand and as an individual product. What is your visual brand language (VBL)? Do you have one? Our RO Designers are practised at working with clients to define their VBL, ensuring continuity of product lines and the correct message, aesthetic and feel when your product ends up in the hands of the end-user.

CMF is a powerful tool that should be used to its full potential, it can make or break great products, and transform the mundane into the amazing.

Find out more about CMF design at Raymont-Osman or get in touch to see how the RO Team can work with you to define your next product line.